Even the ocean cannot be trusted any more. As you sit beside one of the golden empty beaches along the island’s west coast, waves lapping at the foot of funky guest-houses and fresh-fish restaurants, it’s hard not to notice the chalk mark, very high up on the wall, that recalls when the waves came in–and in and in, without stopping–only 20 months ago, and swept away 36,000 people across the island, leaving 443,000 without homes. Sometimes Sri Lanka seems to be almost a parable about the frailty of hope. When peace broke out in 2002, foreigners began streaming into the atmospheric Dutch fort in Galle, turning old buildings into $400-a-night hotels, and stylish galleries selling $130 scarves. “This could be the next St. Tropez,” a British hotelier told me.

Within five weeks of the opening of the chic Galle Fort Hotel and the super-luxury Aman resort that brought a new phrase (“boutique hotel”) into the local lexicon, another word rushed in.

“At first I just thought it was a tap that was broken,” says a villager never Galle. “I had never even heard this word `tsunami.’ Only one time, I had read something like that in a Buddha story. And then I saw tables, files, chairs being swept away on Pedlar Street. Buses overturned. I lost my home, but my family ran up to a temple, and they were safe. I went to the hospital and the bodies were piled up like timber.”

When finally the island began to pick itself up after the tsunami, the new hard-line government came in, and fighting resumed.

What makes this more poignant is that it’s not hard at all to see and feel the paradise that’s just out of reach here. Get into a rusty old train for Kandy, and you watch sylvan scenes unfold in unfallen shades of green and gold. Children in spotless white uniforms are walking down red-dirt roads to school, and men, waist-deep in rivers, are waving at the train. The signs along the tracks say, sweetly, “SPEED 5 M.P.H.” There is a languorous tropical sway to the place, a lilting, straight-backed rhythm that makes it feel like India slowed down and stretched out, in a reclining chair overlooking the sea.

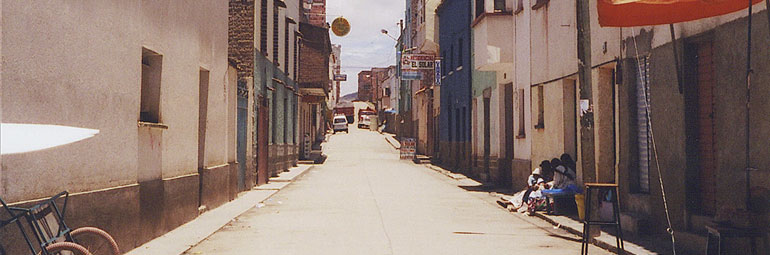

For miles on end, the main road, like the railway, travels between coconut-palm, poster-ready beaches on the one side and thick jungle on the other. And latter-day Polos are in evidence even during war. At the mysterious rock-palace of Sigiriya, “bellas” and “bravissimas” sweeten the air as a local villager leads groups of Italian tourists up the steep incline, bubbling away at them in confident Italian. “Italian Inspiration” furniture sits in the stores of Colombo, and Italian families run a Dream House guesthouse on Unawatuna Beach, and a place called the Full Moon. Near Tangalle on the south coast there is an Il Camino Restaurant (with “Italian Management”).

In certain ways, the sea lanes are bringing waves of the same visitors they’ve always brought. High above Kandy, in a luxury resort, the often deserted hallways suddenly fill up with black-veiled women from Arabia, their trim, bearded husbands gamely asking for pork sausage without the pork. At a remote tea plantation near the misty British hill station of Nuwara Eliya, a minivan opens up and three Chinese sightseers tumble out. Even in the newspaper that features a whole page 2 devoted to grisly color photographs of the suicide attack on Kulatunga, the facing page blithely announces, “Refreshing Sri Lanka a huge success!” (of a trade fair in London).

Sri Lankans themselves, however, are, like Adam, putting paradise behind them. Everywhere one sees ads for dentistry courses in Russia, jobs in Saudi Arabia, even pre-med courses in Romania and places in one Dream Harvest College in London. Qatar Airways runs fourteen flights out of the island every week. The unfortunate, caught in recent fighting around the gorgeous harbor at Trincomalee, take shelter in woods, in churches, under bridges, walking across checkpoints in long lines every morning to get work. The fortunate tell you of brothers in Greece or job offers in Israel–even of the fishermen north of Colombo who have earned so much in Europe that they come back and build a settlement known as “Little Italy.”

To travel along the ocean in Sri Lanka is to pass a confounding mix of places called the Paradiso Hotel, Villa Paradise and the Eden Resort, and headstones by the dozen on the sand. And many of the billboards offering news of projects run by organizations from Japan, Austria, even Jersey tell you that new schools, hospitals, multi-story apartment blocks have been “Funded by the Italian People.” Yet not even good will can escape the long shadow of politics in Sri Lanka today. Of the 14,650 houses that need to be built in the wake of the tsunami, according to authorities in Galle district, barely 10% have been completed in 18 months. The lavish aid that flooded in from around the world is said to have disappeared into private accounts, or even to have been used for military purposes.

Those who remain can only try to keep their heads down and their bets covered–like the tuk-tuk driver who brandishes pictures of Buddha on the roof of his vehicle, stickers of various Hindu gods and a large depiction of the “Natural Mystic” Bob Marley. A local Buddhist group has put up slogans all around Colombo, among the Chinese halal restaurants and casinos, saying, “Grief is born of craving” and “It is difficult to be born a human.” And around the artificial lake in Kandy, built to give an air of Buddhist tranquility to the old capital, someone has scrawled up on a wall, “V will do beterest in Colombo.” The meaning of the slogan is clarified by a nearby message, from a different hand, “Who ever said that the Lion is the king ?”

Two days after the Kulatunga killing, a police officer is questioned on grounds of spreading false alarms. “Rumor-mongering” is now an imprisonable offense, a national paper shouts on its front page (while on its inside pages, it and its rivals spread further rumors of a coming attack on Galle harbor, another raid on the airport, child assassins being trained to infiltrate schools). If spreading false word could land one in prison, Marco Polo might be serving a life sentence–or two–in the country he so raved about from afar.