Other friends try to go on long walks every Sunday, or to “forget” their cell-phones at home. A series of tests in recent years has shown, Nicholas Carr points out, that after spending time in quiet rural settings, subjects “exhibit greater attentiveness, stronger memory and generally improved cognition.” Their brains become “both calmer and sharper.” More than that, empathy, as well as deep thought, depends (as neuroscientists such as Antonio Damasio have found) on neural processes that are “inherently slow.” The very ones our high-speed lives have little time for.

In my own case, like most of us I turn to eccentric and often extreme measures to try to keep my sanity and ensure that I have time to do nothing at all (which is the only time when I can see what I should be doing the rest of the time). I’ve yet to use a cell-phone and I’ve never Tweeted or entered Facebook (though in Estonia a few months ago I encountered for the first time a country where public phones are more or less extinct, and realized that the writing is on the screen for the likes of me). I try not to go online till my day’s writing is finished, and I moved from Manhattan to rural Japan in part so I could more easily live without a TV I can understand and every trip to the movies would be an event.

None of this is a matter of principle or asceticism; it’s just pure selfishness. Nothing makes me feel better—calmer, clearer and happier—than being in one place, absorbed in a book, a conversation, a piece of music. It’s actually something deeper than mere happiness: it’s joy, which the monk David Steindl-Rast describes as “that kind of happiness that doesn’t depend on what happens.”

It’s vital, of course, to stay in touch with the world, and to know what’s going on; I took pains this year to make separate trips to Jerusalem and Hyderabad and Oman and St. Petersburg, to rural Arkansas and Thailand and the stricken nuclear plant in Fukushima and Dubai. But it’s only by having some distance from the world that you can see it whole, and understand what you should be doing with it.

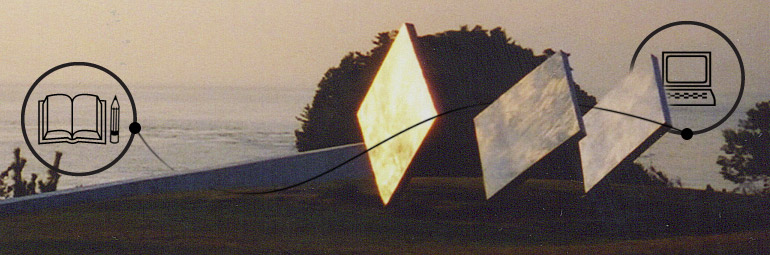

For more than 20 years, therefore, I’ve been going several times a year—often for no longer than three days—to a Benedictine hermitage, 40 minutes down the road, as it happens, from the Post Ranch Inn. I don’t attend services when I’m there, and I’ve never meditated, there or anywhere; I just take walks and read and lose myself in the stillness, recalling that it’s only by stepping briefly away from my wife and bosses and friends that I’ll have anything useful to bring to them. Around me are real-estate salespeople, teachers, actors, executive vice-presidents. Silence, we find, is as ecumenical as a car servicing–and has much the same effect, in terms of preparing us for the rough roads and traffic jams ahead.

The last time I was in the Hermitage, three months ago, I happened to pass, on the monastery road, a youngish-looking man with a 3 year-old around his shoulders.

“You’re Pico, aren’t you?” the man said, and introduced himself as Larry; we’d met, I gathered, 19 years before, when he’d been living in the cloister as an assistant to one of the monks.

“What are you doing now?” I asked.

“I work for MTV. Down in L.A.”

We smiled. No words were necessary.

“I try to bring my kids here as often as I can,” he went on, as he looked out at the great blue expanse of the Pacific on one side of us, the high, brown hills of the Central Coast on the other. “My oldest son”—he pointed at a 7 year-old, running along the deserted, radiant mountain road in front of his mother—“this is his third time.”

The child of tomorrow, I realized, may actually be ahead of us, in terms of sensing not what’s new, but what’s essential. As I took my leave of the cheerful family, I knew what one at least of my New Year’s resolutions would have to be this coming year.