Part of what fascinates so many in Cohen is the mixture of intimacy and elusiveness; few writers render themselves so seemingly open and unadorned on the page and yet few offer so rich a sense of having no interest in explaining anything away. It’s as if—like many of our deepest artists, from Emily Dickinson to Melville—the more Cohen sits still in a room, plumbing the secrets of the interior, the more he sees how much externals are beyond his grasp. If he’s always evinced a keen, tough-minded, unyielding interest in control, it’s because he knows how much cannot be controlled, in love or faith or solitude.

One of the beauties of Silvie Simmons’s new book, I’m Your Man, which instantly becomes the definitive sourcebook for all material on the man, is that she brings to Cohen much of the discretion, perceptiveness, tight focus and wit that he brings to the world; the deeper strength is that she doesn’t just dig up Cohen’s water-safety certificate in summer camp, or point out that he recorded parts of his first album in the same converted Greek-Armenian Orthodox Church where Miles Davis recorded “Kind of Blue.” She’s traveled everywhere to speak to more than 100 of the singer’s oldest associates. Nearly every one, whether childhood playmate or former lover, cousin or even record producer, independently presents us with a portrait of an uncommonly courtly, gracious and impeccable soul who’s never liked to be at the center of attention and who, having grown up with great wealth and expectation, has always hungered for less.

“He’s humble, but also fierce,” says Rebecca de Mornay, his onetime love. “He has this subtext of `Let’s get down to the truth here. Let’s not kid ourselves.’ “ Or, as Marianne Ihlen, the Norwegian beauty who shared a simple room on the Greek island of Hydra with him, has it, “He was a gentleman, and he had that stoic thing about him and that smile he will try to hide behind. `Am I serious now or is all this a joke?’ “ If a man is known by the company he keeps, Cohen seems to have found—or helped encourage—people who reflect back his elevation and determination to see things on a larger canvas. And he has remained as unswervingly loyal to them as they, in pretty much every case, have been to him.

He was raised, as Simmons aptly points out, “in a house of suits,” his father the very proper owner of a high-end clothing business who became one of the first Jewish commissioned officers in the Canadian Army, his mother a Russian rabbi’s daughter who was warm, volatile, and occasionally subject to depression. That mix of formality and emotionalism is what gave his work its edge, its polish from the beginning; here was a passionate man in a fancy suit. And his deep sense of connection to his priestly forebears—his grandfather was president of a synagogue– seems to have left Cohen with an innate respect for discipline and ceremony, the steadfast Judaic roots that have allowed him to bring Jesus and the Buddha and St. Paul into his songs of longing.

It’s not hard to feel, in fact, that he was made for the Zen life from the outset, with his devotion to ritual and order, his love of simple spaces, his concentration upon essentials. Part of what makes him so hard to catch is that he’s always one step ahead of you in his thinking (dismissing “charismatic holy men” just as you’re about to accuse him of following—or even being—one); but what keeps him so close to us, what allows us to feel he’s speaking to us, is the directness with which he takes that very tendency to task.

The other force that formed him, surely, is Canada, which gave him the ideal grounding in mixing Old World and New or, in Simmons’s nice phrase, “archaic language…with contemporary irony.” He’s always seemed to live at a distance from himself and been ready to play with masks in a way that’s less familiar—threatening, perhaps—to many below the 49th parallel. Those who have thrilled to his recent tours may be surprised to learn that both stage fright and a genuine lack of confidence in his singing have often made live performances an ordeal for him, perhaps because he’s not into shows and performances; before his first tour, he had his oldest friend, a sculptor, make a mask for him—a “live death mask,” in Simmons’s phrase—though in the end he never wore it, perhaps because he’d perfected a persona that was distraction enough.

After his father died, when Cohen was nine, he was left in a house of women (his sometimes mercurial and, as he put it, “Chekhovian,” mother and his elder sister); in his yearbook at Westmount High School (where he was a cheerleader), he wrote: “Ambition: World Famous Orator…Prototype: the little man who is always there.” Not long thereafter, falling in with a group of raffish Montreal writers, he established himself within a few years as the country’s leading young poet and a wild Joycean novelist.

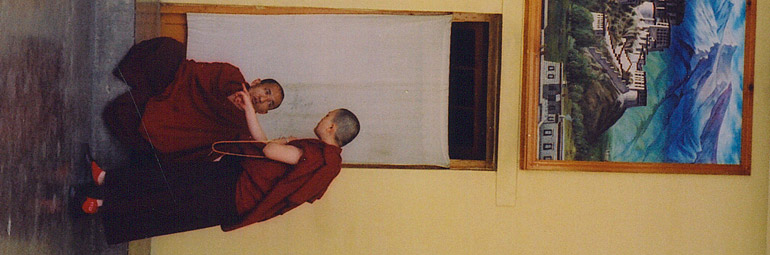

He’s only been comfortable, it’s tempting to think, when stuck in no set position, far from any fixed self: the first time he met Joshu Sasaki, the small Zen master, now 105, who set up the first Rinzai center in the U.S., Cohen was most impressed that the roshi spoke at a friend’s wedding about the Ten Vows of Buddhism, one of which forbids drugs and alcohol, and then devoted himself to drinking down one cup of sake after another. When recording in Nashville, Cohen used a Jew’s harp on more than half the cuts he made; touring with his back-up group across Europe in 1979 and 1980, he would lead the others in a monastic chant in Latin—“Pauper Sum Ego” (“I am a Poor Man”)–while Sasaki Roshi sat quietly reading in one corner of the tour bus.