In his great book of changes and home-made koans, Silence, John Cage defines the purpose of music. “Music is edifying,” the devoted student of D.T. Suzuki wrote, “for from time to time it sets the soul in operation. The soul is the gatherer-together of the disparate elements (Meister Eckhart), and its work fills one with peace and love.” We have, of course, Soul Music—who can resist the transports of the Reverend Al Green or Aretha Franklin?—but we also have a more reserved and serene music of, for (and from) the soul. As Cage notes a little earlier in his book, a musician once wanted to give up his art and become a full-time disciple of Swami Ramakrishna. “Remain a musician,” his teacher said. “Music is a means of rapid transportation.”

The music of Leonard Cohen is not notably rapid; a friend recently told me that hemistakenly played a Billy Joel record too slow, at 16 r.p.m., and the result sounded uncannily like Leonard Cohen. And Cohen’s music is not obviously transporting, in the way that U2 can be, with their building chords of imminence, or the otherworldly, post-verbal soundscapes of the Icelandic band Sigur Ros. Cohen takes you in, not up. Some might even say his songs are not always music; my Japanese wife runs out of the room whenever I put on late Cohen because to her it sounds too much like the Buddhist chanting she grew up hearing through the hills of Kyoto at dusk.

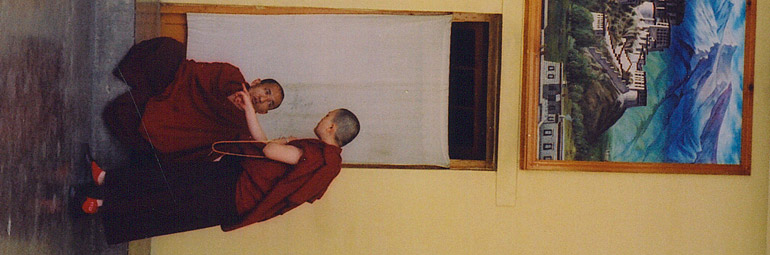

But Cohen’s gatherings-together are unambiguously about the soul, its terrors, its betrayals, its hesitations, its longing to give itself over. A casual listener notices how often the singer uses the word “naked,” most often of women; a fledgling Cohenite hears that he’s saying, “I need to see you naked in your body and your thought”; but the person who lives with the songs realizes that what makes the writer special is that he’s not rendering others naked, but himself. After he met the Zen master Joshu Sasaki Roshi—in 1969, just as he began his recording career—and began sitting with him, Cohen’s commitment to silence and obedience grew so strong that, by 1984, he was giving us his plangent, classic psalm, “If It Be Your Will,” in which (like Ramakrishna’s disciple) he seemed ready to give up even the speech and song by which he offered himself to the world if his master so wished.

“Soul” is not a word to use in Buddhist discourse, but there’s no doubting that Cohen would echo many of the sentiments of that other unsparing Zen student, Cage: “People say sometimes, timidly: I know nothing about music but I know what I like. But the important questions are answered by not liking only but disliking and accepting equally what one likes and dislikes. Otherwise there is no access to the dark night of the soul.”

Or, as Cage put it more succinctly: “I have nothing to say and I am saying it.”

It’s one of the unexpected beauties of the age that Leonard Cohen, rather suddenly, has begun to enjoy his fourth—or fifth—Indian summer, to the point where everyone I run into, from Singapore to Melbourne and Kyoto to New York, seems to be talking about him or attending to his messages in the dark. For those who have begun to despair of our celebrity culture, it’s a typically Cohenesque instruction in the deeper meaning of culture and the dismantling of celebrity. After he found out, in 2005, that his longtime, much-trusted manager seemed to have made off with nearly all his savings, rendering him a poor man, he went on the road again, at the age of 73, and performed 250 three-hour concerts from Istanbul to Hanging Rock, deep into his seventy-seventh year. The more he deferred to his accompanying musicians on stage, the more audiences were moved and impressed with him (a rock star who was offering humility and attentiveness?); the more he sang, unflaggingly, about sickness, old age and death, the more listeners started taking him as a guide to life, the rare spiritual being who didn’t seem to be peddling any creed or presenting himself as anything other than mortal.

In his mid-seventies, his old song “Hallelujah” took over the number 1 and number 2 spots in the British charts, and a host of “American Idol”-style cover versions made it the fastest-selling Internet download in European history; the record that he made last year, with the deliberately ungrabby title of Old Ideas, was number 1 in 17 countries and reached the Top Five in 9 others. The result has been incongruities as rich in irony and surprise as any of Cohen’s songs about the future: I woke up amidst the glittery singles bars and temples to conspicuous consumption of the L.A. Live entertainment center at the heart of L.A. last year and, walking into Starbucks, was greeted by the album being featured that week: the work of an ordained Zen monk mumbling of how “None of us {is} deserving the cruelty or the grace.”

Every day now brings news of a fresh book on the man, in French, in German, in Spanish; in 2009 the former editor of the Guinness Book of Records, Tim Footman, brought out a small biography full of classic Cohenesque tidbits, whose discography alone took up 28 pages, not least because Cohen has already inspired more than 50 tribute albums worldwide. Thirteen years before that, the Canadian professor of literature Ira Nadel came out with a biography assembling many of the facts and starting with a quote from Kierkegaard (“What is a poet? A poet is an unhappy being whose heart is torn by secret sufferings, but whose lips are so strangely formed that when the sighs and the cries escape them, they sound like beautiful music”).

When people learn that I’ve been lucky enough to spend a little time with the man, they often want to hear more. All I can say is: “He’s like one of those old Eastern poets of whom he’s been writing for half a century or more. Alone in his simple hut on the top of a mountain, with a pen and paper and a bottle of wine (perhaps a beautiful woman) nearby.”