Though talking to foreigners is forbidden, a tourist alone presents an irresistible target. A phone rings in his hotel room, and a girl the visitor has never met professes eternal love, leading, no doubt, to a quickie marriage and a ticket out. A government worker takes him aside and asks, with great diffidence, if he would mind very much having his passport stolen. “Nobody is happy, but everyone is afraid to speak out,” observes a habanero. “Nobody trusts anybody else. A few years ago, a generation arose that wanted reform. ( Now the main preoccupation is keeping quiet. People are waiting to see what will happen when Fidel goes.”

One dissident recalls a late-night knock at the door. A mild-looking young official stood outside with a request: “We want you to come and do three months of military service.” “If I do,” said the dissenter, “I will lose my job.” “No problem,” said the recruiter. “We will take care of you.” The uninvited visitor ultimately agreed to go away, indicating that some free choice still exists in Cuba. But that the summons can come at all shows just how fragile that freedom remains.

While the typical Cuban struggles to live off his various resources, he cannot fail to notice that his leader is spending lavishly on grand public relations flourishes: building giant convention centers, inviting outsiders to inspect the Revolution at government expense, sending more than 800 athletes to Indianapolis for the Pan American Games last month. Even malcontents, however, are often willing to absolve their boss of the blame. “The Bearded One is a good man,” says a critic of the government. “He understands everything. But the people around him are no good.” Like many comments, that implies a deep anxiety about what will happen if Castro is succeeded by his less charismatic, more dogmatic younger brother Raul, currently Commander in Chief of the armed forces.

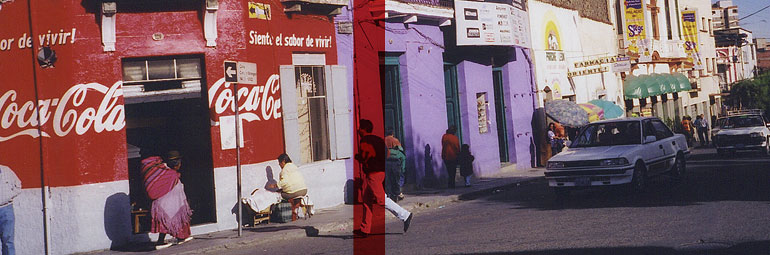

In spite, or maybe because, of all the discordant bass notes, the government constantly tries to drum up new support. Billboards, telephone poles, even entire buildings are awash in exhortations: NOW IS THE HOUR OF SACRIFICE; THE FIRST DUTY OF REVOLUTION IS TO WORK; TODAY WE ARE PROTAGONISTS IN AN AGE WHEN EVEN THE EVERYDAY CAN BE HEROIC. Earlier this year, half a block in Vedado was given over to a multicolored Communist Youth pavilion pulsing with catchy rock tunes. More recently, small towns across the country were plastered with posters declaring, IT IS ALWAYS THE 26TH, in honor of the anniversary of the Revolution’s opening shot on July 26, 1953.

Castro reserves his most strident gestures for his neighbor across the water. Immediately opposite the U.S. Interests Section in Havana, a branch of the Swiss embassy staffed by 20 Americans, a neon sign featuring a caricatured version of Uncle Sam and a Cuban guerrilla still flashes the message MR. IMPERIALISTS! WE HAVE ABSOLUTELY NO FEAR OF YOU! Turn on the TV on a typical day, and you will find a documentary about Mafiosi drug lords in the South Bronx. Go to a bookstore, and the main specimen of English literature on display is The Godfather.

Not surprisingly, many citizens feel insulted by what one calls “these prerecorded tapes the government tries to play in my head.” In private, they prefer to swap rumors about their leader or insult his Soviet patrons. Asked if he learned Russian in school, a church worker exclaims, “I would rather die!” Grumbles a construction worker nearby, “I would never buy anything Russian. You might as well throw your money away !”

The flip side of that preference, and surely the most subversive fact of life in Cuba, is the simple, tantalizing closeness of the U.S. Donald Duck stickers are a status symbol everywhere in Havana, and audiences cheer on the Goonies with much more gusto than the propaganda shorts that precede the feature film. At a local baseball game a foreign service officer asks desperately for the latest about the New York Mets’ Dwight Gooden. Almost everyone has a close friend, an uncle, even a parent in the U.S., whose reports of the affluent society they are not inclined to write off as propaganda. Small wonder, then, that in June alone more than 50 Cubans splashed ashore in Florida, while almost simultaneously two of Castro’s top aides defected to the U.S.

Not all young Cubans are hostile to their system. “Look at me,” says a nattily dressed, blond 24-year-old who spent two years stationed in Angola. “Do I look like the kind of guy you Americans call a mercenary? Do I have horns on my head? Sure, we have problems over there, just like you guys did in Viet Nam. But we had help from the East Germans and others in our Revolution, and it is our turn to help others. It is important that we repay our debts.”

For such firm loyalists, ideology knows no borders. “I think Bruce Springsteen is a blind nationalist,” proclaims the former trooper in the easy drawl he has copied from Florida deejays. “Sure! Just look at that title, Born in the U.S.A.!” Even here, though, things are not quite as clear as they seem. In the ex-soldier’s spacious home off once splendorous Fifth Avenue, a picture of Che Guevara stares across at an equally large poster of Barry Manilow. Downtown in central Havana, a 15-year-old schoolgirl goes him one better. On top of her dresser she has carefully fashioned a collage of her three great heroes: Michael Jackson, Jesus and Che. Thus the unlikely eclecticism of Cuba’s revolutionary experiment.