“The minimizing of entry red tape reveals that you are expected and welcome to this land of gorgeous adventure and the limber elbow,” notes the 1938 Blue Guide to Cuba in summoning Americans to the nearby island. Nowadays, of course, the situation is different. For more than two decades, Cuba has been virtually off limits to U.S. citizens. Recently, however, TIME Contributor Pico Iyer was able to spend roughly three weeks as a tourist on Fidel Castro’s island on two separate trips. His impressions:

The studio apartment is hidden away amid the rambling old Mafia hotels and quiet leafy parks of Vedado, Havana’s modern midtown district. Like many a Cuban home, it has a dusty attic quality, the poignancy of a well-cared-for poverty. The apartment’s contents are fairly typical. A high shelf has been turned into a home-made altar, crowded with Catholic icons. Below is a shelf stuffed with the works of Spinoza, Graham Greene, Raymond Chandler. Between the two is a huge black-and-white TV set on which, boasts its owner, he can sometimes catch programs from the U.S. All through the place a ceaseless whine crackles out of a bright red Phillips boom box, bought under the counter for $800 and tuned now to Radio Marti, the anti-Castro station run by Cuban exiles in Miami. Every now and then, the hum of the half-jammed station is drowned out by the squawks of a rooster named Reagan. Why Reagan? Because, says his keeper, his alarms, unlike those of certain local leaders, are brief and to the point.

The studio apartment is hidden away amid the rambling old Mafia hotels and quiet leafy parks of Vedado, Havana’s modern midtown district. Like many a Cuban home, it has a dusty attic quality, the poignancy of a well-cared-for poverty. The apartment’s contents are fairly typical. A high shelf has been turned into a home-made altar, crowded with Catholic icons. Below is a shelf stuffed with the works of Spinoza, Graham Greene, Raymond Chandler. Between the two is a huge black-and-white TV set on which, boasts its owner, he can sometimes catch programs from the U.S. All through the place a ceaseless whine crackles out of a bright red Phillips boom box, bought under the counter for $800 and tuned now to Radio Marti, the anti-Castro station run by Cuban exiles in Miami. Every now and then, the hum of the half-jammed station is drowned out by the squawks of a rooster named Reagan. Why Reagan? Because, says his keeper, his alarms, unlike those of certain local leaders, are brief and to the point.

The owner of the tiny cell, a government worker, acquired it through a bribe and maintains it with the extra money he has made surreptitiously taping and transcribing each week for five years the American Top 40 Countdown, broadcast on a commercial station in Florida. By day he serves his country; by night, like many young Cubans, he dreams of escape. “If ever I get to the U.S.,” he says with a wistful smile, “I could get a job in Hollywood. All my life I have learned how to act. Sometimes I smile inside, it is so crazy.”

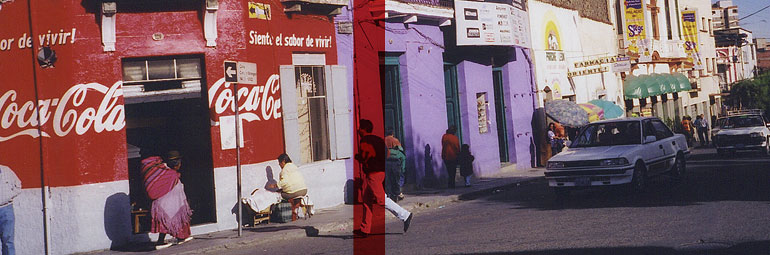

The qualities that hit a visitor most forcibly on arrival in Cuba are its beauty and its buoyancy: the crooked streets and sunlit Spanish courtyards of Old Havana; the chrome-polished 1953 Chevrolets that croak along tree-lined streets past faded but still gracious homes of lemon yellow, orange and sky blue; the warm breeze that comes off the sea at night. In contrast to the gray functionalism of other Communist countries, Cuba is, after all, a decidedly Caribbean island of gaiety and light. On balmy nights, the sound of rumbas pulses through Coppelia, the central park, where brightly dressed teenagers strut around in love or else in search of it. On a brilliant Sunday afternoon in spacious Lenin Park, a steel band lays down a lilting beat and khaki- uniformed officials wave their caps in time to the music. Yet beneath the infectious island rhythms, there is a sad, steady whisper. “If there were no sea between us and the U.S.,” says a musician under his breath, “this place would be empty tomorrow.”

The qualities that hit a visitor most forcibly on arrival in Cuba are its beauty and its buoyancy: the crooked streets and sunlit Spanish courtyards of Old Havana; the chrome-polished 1953 Chevrolets that croak along tree-lined streets past faded but still gracious homes of lemon yellow, orange and sky blue; the warm breeze that comes off the sea at night. In contrast to the gray functionalism of other Communist countries, Cuba is, after all, a decidedly Caribbean island of gaiety and light. On balmy nights, the sound of rumbas pulses through Coppelia, the central park, where brightly dressed teenagers strut around in love or else in search of it. On a brilliant Sunday afternoon in spacious Lenin Park, a steel band lays down a lilting beat and khaki- uniformed officials wave their caps in time to the music. Yet beneath the infectious island rhythms, there is a sad, steady whisper. “If there were no sea between us and the U.S.,” says a musician under his breath, “this place would be empty tomorrow.”

As Castro’s Revolution shuffles through its 29th year, many Cubans are surprisingly ready to voice, however quietly, their impatience with a system that still seems stranded in its noisy infancy. Almost no one would deny that health and education, both free, have improved considerably since the days of Dictator Fulgencio Batista. Grinding poverty has been erased. Drugs and prostitution, which flourished when the place was a raffish offshore playground for Americans, have now gone underground. But in the face of those advances, the man in the Havana street is still unable to speak or travel as he pleases. Money is more than ever in desperately short supply. “Cuba is suffering an economic crisis of massive proportions,” says a foreign diplomat. “Here is a country with no free press, no opposition parties, no capital flight, a controlled economy and $4.6 billion from the Soviets each year — and they’re still, in hard-currency terms, almost bankrupt.”

That chaos is everywhere apparent. Though Cubans have to pay only about 10% of their salary for rent — often barely $10 a month — they must spend twice as much just to buy an imported deck of playing cards. Block-long lines of people wait nine hours through the night and six hours more to get into the Centro department store, still commonly known by its prerevolutionary name, Sears, where government surplus items are sold at extortionate prices ($2 for a small bar of chocolate). “We have some good news and some bad news,” runs the local joke. “The bad news is that everyone is going to have to eat stones; the good news is that there are not enough to go around.”

With money scarce, and goods even scarcer, a diplomat observes, “crooked deals multiply until they ensure that the economic plan can never work.” Some people take photos, fix jalopies or do typing on the side; others simply try to resell the goods they manage to procure. The rampant finagling is only encouraged by a bureaucracy with so many hands that none is likely to know what the others are doing: in a Havana telephone directory, the list of ministries takes up 77 pages.